Last week, I saw this tweet here about percentages changes:

It’s a very legitimate problem, because communicating changes in percents is actually very difficult. I’ve grown very numb to it over the years of my career, but if I sit down and be very honest with myself, I find that I have a messy set of heuristics for using percentage numbers when communicating change. They work in certain contexts, but break down in all sorts of ways when you’re not careful.

So let’s reflect a bit on this super common, but sub-optimal way of communicating changes.

The TL;DR — my rough heuristics for communicating with percentage changes

If the metric tends to move fairly steadily, either due to smoothing or is naturally low-noise, percent changes is rarely a problem. You can even plot the percent change curve if you want and it’ll highlight volatile points

For noisy, volatile data that can’t be tamed with smoothing methods, showing percent changes comparing points in time can be useful for context, but plotting the historic percent change line tends to be less useful. Just directly discuss the trend if that’s of interest

It’s rarely useful to use percent changes when the base number is a percent or ratio. It’s much easier to quote changes in percentage points or actual concrete numbers.

If your audience is sophisticated, or you take the time to educate your audience, you can use log scales too

You’ll note that on average, I’ll wind up showing percent changes quite often, because for “well-behaved” data sets they’re more useful than not. But there are very specific situations where things will fall apart

First, why do we normally describe things with percent changes?

The use of percent changes is everywhere in industry. Percent changes are valued because they provide useful context, represented as a single number. Everyone is accustomed to their use and don’t really question why they’re there and how they’re calculated.

The context the number provides proves to be quite useful in many situations. Revenue going up $10 million in a month might sound like a lot of money, but it gets a very different reaction if that represents just a 0.1% change compared to last month. The base intuition is that small percent changes are less interesting, while big changes often indicate something important is happening that may need attention.

It’s the rare combination of being universally understood, easy to calculate, and capable of providing useful context in many situations that leads to them being used everywhere.

But, where do percent changes fail?

The biggest, most often encountered is that percentage gains and losses don’t cancel each other out intuitively. A 50% loss of sales one week requires a 100% gain in sales the next week just to get back to the same absolute point. The math only gets more difficult to mentally calculate when its not round numbers.

Another common flaw is that when the denominator is small, percent changes look ridiculous. You know, the “metric goes from 1 to 3, that’s a +200% change!!” thing. It’s pretty rare to find someone in industry get excited over that 200% once they realize what the absolute change was (though it does happen). But even if you try to avoid this situation, if you happen to be displaying percent changes in an automated email or dashboard, you can accidentally hit upon this problem of ridiculous-sized percent changes.

Another lesser issue is that while percentage changes provide context for a number by comparing against another number in the past, it only provides comparison with a snapshot in the past. I spent the first couple of years of my career chasing down huge +30%, -40% Year-on-year changes to an important metric only to found out that the Easter holiday was on a different calendar date and thus all activity was just higher/lower respectively.

Then, people can make things worse

Sometimes, people request things that amplify the flaws of percent changes. For example, some people would like to see a historical plot of the percent changes over time. They obviously want to place the percent change within historical context because they’ve been burned by the single snapshot before.

The problem with plotting historical percentage changes is that you’re plotting essentially a derivative of a somewhat random variable. There’s absolutely no guarantee that your metric behaves like a smooth function, so your percent change function can bounce all over the place. Such graphs are hard make any sense of at all.

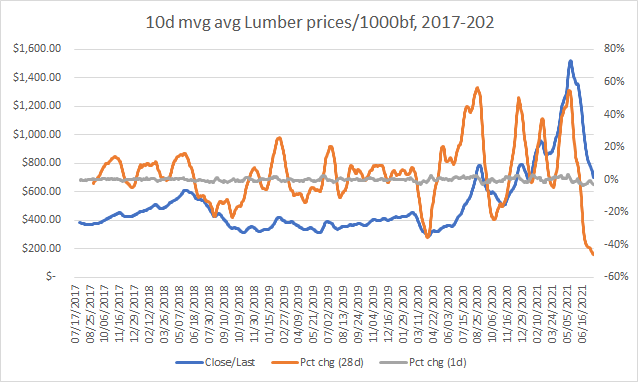

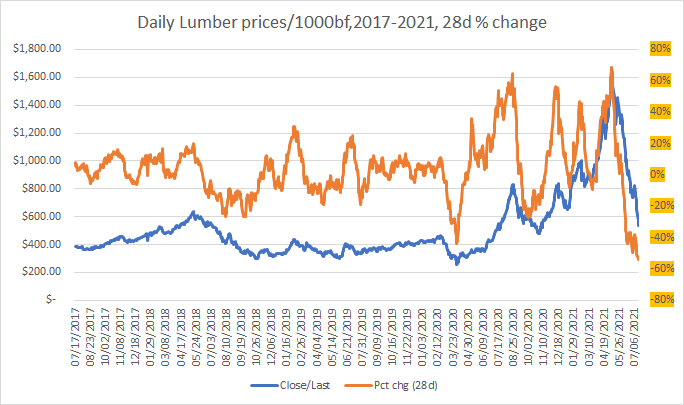

Here’s an example of such a graph, daily lumber futures prices, which had gone a bit crazy during the pandemic. The blue line is the absolute number of dollars a unit of lumber costs (1000 board feet), and the orange line is the day’s price compared to the price 28 days prior. I picked the range arbitrarily.

Note that the orange secondary axis is scaled so that 0% growth is in the center. The orange line is extremely difficult to interpret. It flies up and down, above and below zero with a lot of volatility.

Situations where percent changes work better

While quoting percent changes seems like a really silly thing to do given all the difficulty surrounding it, it’s still used everywhere, throughout the data and business world. The reason seems to be that while percent changes are prone to misbehaving, they’re “good enough” for a very narrow band of use cases.

Essentially, if the snapshot nature of the comparison gives sufficient context to the audience (for example, many year-on-year comparisons), and the percent changes are fairly stable (as in, they don’t change sign too often), things can work out.

In my experience, percent changes work well for stuff that moves within a narrow band that people already expect, and deviations are obvious and notable. For more established businesses, revenue numbers very often fall into this category — money tends to flow in at fairly predictable rates. Other examples are large aggregate measurements of slow-moving things like inflation.

Well, that’s a really restrictive set of conditions…

While some data is typically well-behaved enough that quoting percent changes usually doesn’t lead to much confusion, that is obviously not true for most bits of data. Most data does not come in a “fairly stable” state. Everything has some random noise inside it, but very often the amount of noise is significant enough that it makes life hard. So we need to manipulate our data a bit to smooth out those issues.

The first thing to do is to simply smooth the time series out by using things like moving averages or moving sums. These smoother series will have smeared out much of the noise lurking in the data, which might help with things.

The orange line still exhibits a huge amount of fluctuation… but lumber did go pretty wild since the pandemic. I’m unsure how useful it is to know that prices had jumped up ~40% since a month ago, but I also can’t say it’s useless either. This would wind up being a case where the percent change GRAPH is pretty useless (because how do I process that wiggly line), but the spot percent change quotes carry some utility.

When things really break, the percent changes are more trouble than they’re worth

Going back to my example about how Easter always messes with my YoY metrics comparisons, sometimes having the percentage change around just raises more questions than they’re worth. Everyone always goes “why are we down 30%?!?” in a panic, and calm right down when I go “It was Easter this week last year”. If at all possible I’d just omit the panic-inducing number to begin with. If I can’t (because people are expecting the number) I’d leave an obvious footnote to the effect of “ *Due to reasons, ignore this”.

In that situation, it is almost always easier to talk about things in absolute numbers, or just redirect the entire conversation somewhere useful. You can even make a whole distinct point to talk about where how the absolute numbers are trending, if it weren’t for the pesky holiday messing things up.

When talking about percents, just give up and talk in absolute numbers (aka, percentage points or actual numbers)

Lots of metrics are already ratios, conversion rate being one of them. 40% of people who put things in their cart actually check out!, etc.. It’s probably THE most looked at set of metrics for an e-commerce business, because each conversion means money in the bank.

You are typically faced with the decision of whether to quote an increase in conversion rate from 40% to 45% as either a 12.5% increase, or a 5 percentage point increase.

You’ll typically want to do the latter.

The main use for the 12.5% increase number is useful for is it tells you you can expect a 12.5% increase in top line sales. Except I’ve never really seen revenue numbers track conversion this closely because something else changes downstream within the system and you wind up getting more returns or bad users. You can typically expect MORE sales, but the magnitude is hard to predict.

Meanwhile, if you converted the conversion rate change into percentage points, it’s easier for people to understand the context with simple addition. The rate went up 5 points to 45%, it used to be 40%.That’s a pretty big change because whole percentage point changes are hard to come by. You don’t fewer absurd “+5% is great at 80% base conversion, but +5% is horrible at 1% base conversion” conversations.

To be even more effective and clear, you can actually convert things into concrete numbers — “+5 percentage points in conversions means an extra 460 people a day, which should be an extra $5k in revenue.” Because at the end of the day, the conversion rate is merely a ratio we’re interested in because it affects revenue. This makes it much easier to understand how things affect the final number we care about. It ALSO gives you a chance to model out and revise the effect on revenue so that people have a realistic idea of what to expect instead of an outside percentage guide.

Finally, use some log scales

This tends to apply to certain communities and fields than others, I personally have encountered this in finance (especially stock related stuff), and certain scientific fields — logarithmic scales for charts act like a better expression of percent change. The reason is because on a chart, vertical distance is the same when the percent changes are the same. That is, a 50% increase uses the same number of vertical pixels on a chart no matter what the starting number is. This is great for situations where you want to know whether a change is big or small at a glance, and the absolute value doesn’t matter very much to you.

There’s a couple of problems with this method though.

First, certain numbers don’t work. Most prominently, logarithms don’t work with numbers that go negative (or hit zero). So you can’t use it for all data sets. They’re also not super useful in visualizing ratio/percentage data since most of those values occur within a very tight range.

More importantly, typical audiences of industry are not as familiar with log scales. They usually can understand that the scale is different, but will typically nod politely without understanding how to best read them. You have to put at least put some effort into pointing it out and explaining how best to use them. Sometimes, there’s no time for that kind of education.

But if you’re in a situation where you can get away with using log scales, go for it!

Hopefully this makes the confusing points of when to use percent change calculations slightly less… confusing. It still relies on a lot of judgement on what is likely to create confusion or ambiguity within an audience, but it’s hopefully better than nothing.

About this newsletter

I’m Randy Au, currently a Quantitative UX researcher, former data analyst, and general-purpose data and tech nerd. The Counting Stuff newsletter is a weekly data/tech blog about the less-than-sexy aspects about data science, UX research and tech. With occasional excursions into other fun topics.

All photos/drawings used are taken/created by Randy unless otherwise noted.

Supporting this newsletter:

This newsletter is free, share it with your friends without guilt! But if you like the content and want to send some love, here’s some options:

Tweet me - Comments and questions are always welcome, they often inspire new posts

A small one-time donation at Ko-fi - Thanks to the folks who occasionally send a donation! I see the comments and read each one. I haven’t figured out a polite way of responding yet because distributed systems are hard. But it’s very appreciated!!!