This bi-weekly paid subscriber post of thoughts on Randy’s mind brought to you by a lot of eye rolling.

So a new startup has been making the rounds on my Mastodon feed amongst my UX friends. I’m not about to give them SEO but if you search for the term synthetic user you’ll likely come across it… unless more startups pop up in the next couple of weeks. Considering the climate of AI-hyped startups these days, I would not be surprised if competitors popped up like weeds if it gets any sign of traction at all.

The pitch of said startup is… “User research, without the users”. They use generative AI to create fake synthetic personas… and then have you run your product ideas against said personas and they tell you what they like or don’t like about it.

Why go through the trouble and expense of recruiting and interviewing samples of live humans for a product or usability study when you can ask an infinitely cheaper GPU that won’t tire or need compensation! Generate product ideas endlessly and get feedback. Find product-market-fit in minutes! Get the feedback you need to make product decisions instantly! Do it cheap and fast!

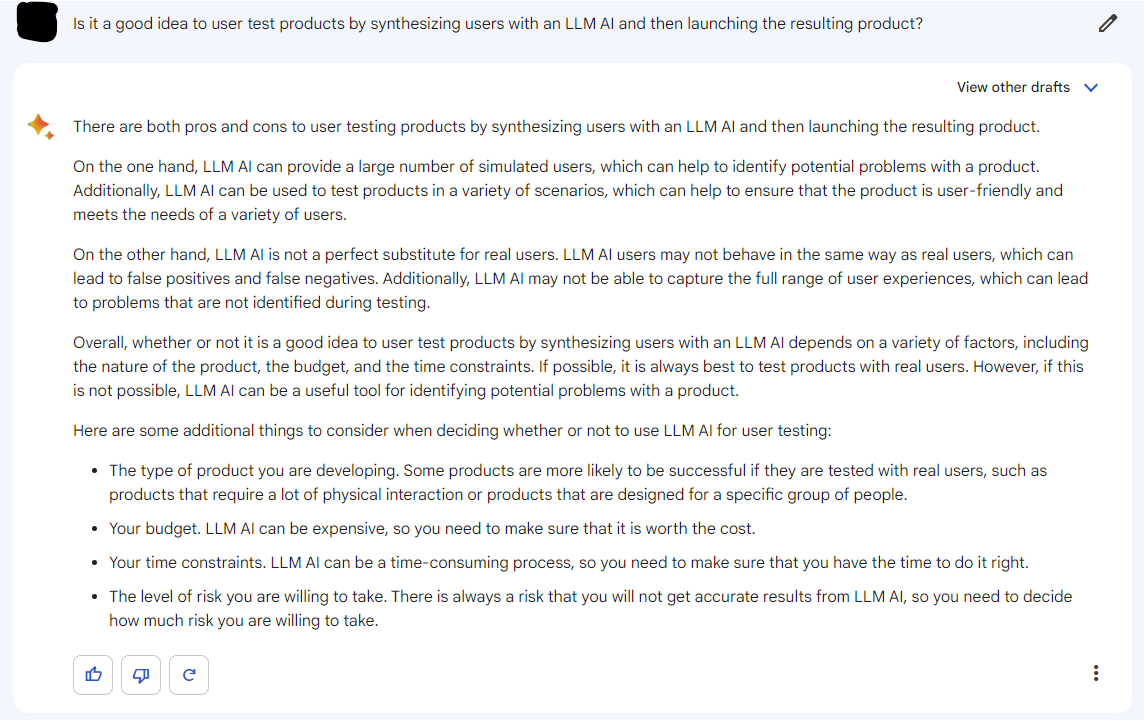

For the hell of it, I asked Google’s Bard what it thought about the idea and it weaseled out with an “It Depends(tm)”. But it did mention the risk of the results being not accurate. Much of its other opinions are fairly nonsensical and premised on me developing an LLM.

The reaction of the UX community was about what you’d expect — a lot of eye rolling and skepticism because the concept is missing the point of user testing. When I showed it to my coworkers, I quipped that it was like having a business without the customers. Another researcher said that while they thought it’s a terrible idea, they might know a couple of product managers who would probably love the idea.

Even if you give way more benefit of the doubt that is probably warranted, the whole concept loses sight of why we need to validate our ideas against real people in the real marketplace to begin with. No amount of imagination and personas can approximate the lived experiences and views of people. In fact, within the UX community, the use of personas, the summarized fictious ‘average people of a certain type’ continues to be questioned as to whether they’re an effective tool to use or not. It’s not clear cut and there are ways to use and abuse researcher-generated personas based on real interviews and studies. You don’t even have to inject LLM-powered fictions on top of it all to be on methodologically uncertain ground.

The whole point of user research is that we’re always surprised by the combined cluelessness AND cleverness of users. People will have needs we’ve never heard of, have work processes we’ve never seen, priorities we can’t imagine, and they will attempt to use our products in ways we never intended. It’s up to us as good product people to take that and decide whether we want to encourage or discourage that behavior in our product.

Hopefully, making the correct choices leads to increasingly happy users willing to pay us money. An LLM that’s effectively the statistical average of all the text on the internet will capture some of this variation and sentiment, but no one knows to what extent and completeness. I have no idea how capable such systems are in expressing unexpected, novel statements.

PMs already try this anyway without LLMs…

Even prior to this whole LLM thing, there have always been PMs who wanted to run their own usability studies. I’ve seen qualitative researchers immediately jump up and volunteer to give training to these folk because, without training, the PMs would often ask questions that are biased towards the end result they wanted. The training was meant to help then avoid falling into a giant confirmation bas trap.

For example, a PM might directly ask whether a user would want a specific feature. Most users would say yes since the PM would likely ask about features that had been requested by others before. But just because a user finds a feature desirable verbally doesn’t mean that it’s exactly the thing that needs to be built immediately — there could be more pressing issues that need addressing. Knowing that a user wants a specific feature doesn’t tell you how to design and implement said feature. Understanding users is more about understanding the motivations behind their actions than any specific action. If we understand people’s motivations, we can much better anticipate what they are likely to do.

And therein lies the danger. When you can summon and tune your virtual users to fit whatever population distribution you want, and they’re all going to mimic some arbitrary “persona” via “the magic of AI”… well, how are you going to do anything except encounter confirmation bias? How can you surprise yourself when you’re largely presenting to a set of people that you’ve specified the fabrication of?

If you ask any of the chat bots whether users would accept some ridiculous product, like “would users want to use a product that gives them electrical shocks”, they’ll probably give the expected answer of “probably not except in certain situations”. But most people typically don’t need an AI to tell you that. Tone things down to ideas like “would a user pay $5 to speed up a wait time by 5 minutes?” and the answers effectively read as “it depends”, which is also the expected answer. If anything, it’s hard to thread the needle to ask these things a question where it doesn’t give an obvious answer, let alone a surprising one.

To the extent that you want to pay for a rubber duck to sound ideas off of until they don’t sound ridiculous, I can totally see it working. It’s just not clear exactly what value it brings beyond that.

Machine Translation, but for UX

So, another market that was disrupted by ML tech a decade or so ago was translation. Machine translation had gotten significantly more convincing over the past decade as new techniques were developed. Things improved enough that people who weren’t familiar with both languages themselves found it very believable. Enough so that students started trying to it on their homework and tests (but teachers can still spot those instances most times).

Translation agencies started leveraging that technology to increase their throughput, effectively taking on more work for little increase in staffing. Some of the less scrupulous outfits would offer cut rates because they’d hire significantly less qualified (read, cheaper) editors to “fix up” machine translated text without correcting obvious language issues. Such texts still come out fairly crappy, but they get something out fast enough to take on tons of work. These agencies can often get away with their shoddy work because clients often can’t read the target languages, so they can’t judge the quality of the work.

End of the day, this behavior put a lot of pressure on the lower end of the marketplace. It’s a lot of work explaining the value proposition of paying a relatively expensive translator compared someone who claims to do it for half the price or less, and faster. The higher end of the market, the legal documents and companies that have experience with translation is less affected because they can still see the gap in value.

It’s very easy to see this play out in the near to mid term if such robo-UX takes root. The same people who are going to think it’s a great and wonderful idea are also the people who aren’t equipped to know where the pitfalls are.

For simple things that seem obvious to experienced UX folk, like not putting huge friction points between users and their desired activity or saying that “users like cheap and secure”, the advice will probably be usable. But for deeper, more complex things, human experts are still going to be needed to do the job and capture the nuance that the computers can’t.

But just as the translation industry can’t stop the technology creating a perverse situation for a certain segment of the market (that arguably might not have been part of the original market for translation services), there’s no force on Earth that will stop people from trying to use what appears to be a cheap and easy solution to their problems. It remains to be seen whether people will find it useful enough to adopt, but these things can go pretty far just on promises and illusion alone.

It’ll be up to us to keep emphasizing the value that we bring to the table as researchers.

No, I’m not looking forward having to that either.