Normconf is over and everyone loved the experienced. I got to have fun being “bullied” by ChatGPT on camera for a couple of minutes and got turned into a slack emote for my efforts. That was completely unplanned (beyond Ben generating ChatGPT content on his own ahead of time) and was great.

The main talk track videos had just been uploaded! Vicki says she’s writing a blog post about her experiences running a surprise successful conference. Obviously her post will be much more informative than anything I could ever write as a volunteer. When it’s out, I’ll be sure to link to it in a future post and hopefully someone will use it as a reference to create their own amazing event in the future.

The one thing I wanted to highlight this week is the value of having a live event. While, for example, Normconf had a set of pre-recorded lightning talks that many people seemed to enjoy (the most viewed talk has over 2600 views as of now), I haven’t seen much in the way of chatter about them aside from the week of release. They’ll now sit there in the long tail of data content, with people finding and watching them slowly over time.

There’s this effect of humans being the social creatures we are, where the fact that a large group of people gathered in one place to watch the same thing, even virtually with other data nerds, has an important value. I have a giant backlog of papers, talks and tabs that I’ve half-promised myself I would get around to consuming in the future. That promise is more likely broken than kept because life is busy and I’m always distracted by something else. It’s the peer pressure of knowing that my data peers are watching the same thing and are currently chatting about it on the Slack in front of me, that forces me to keep my butt in my chair and my attention on the screen.

This peer pressure/FOMO function of conferences feels like a somewhat newer phenomenon thanks to the power of social media. Prior to that, you’d definitely feel like you were missing out on some academic/trade conference, but if you couldn’t travel for whatever reason then you would maybe look at the proceedings that gets published, maybe talk to a colleague that went, and then go on with life. Every event these days is streamed/liveblogged/commented on to the point where you have the opportunity to participate from a distance, so what’s your excuse now? Why aren’t you watching?

I’m sure that old-school in-person conferences had originally been developed for a different social use — it’s for people interested in a given field to travel and get together, meet their peers in the same space, and also provide a forcing function for a bunch of new papers/presentations/ideas to be created and shared at the conference. The side effect is all the interpersonal interaction and relationships being formed.

A virtual conference like Normconf still provides a forcing function for the creation of new content, but since it loses the physical “everyone in the same space” part, something needs to be done to fill the gap. Without some mechanism to get people to feel like they’re watching with other people in real time, the experience changes from being an exciting in-person conference that people pay attention to, to a book of proceedings read with voice-over done by the original authors. One has good side effects of interaction and community-building, the other is just an audiobook by another name.

Tech for feeling together when we’re not

You might think it’s weird that I’m writing about “technology” used to promote the feeling of being together while we’re apart when talking about a virtual live conference. After all, we’re all THERE watching, LIVE, at the same time! How much more together can we be? We all live in an age of endless video meetings already. Don’t we already experience all of it all the time now?

But there’s a long history of this sort of tech in various contexts. The most ubiquitous example being the “laugh track” that comes into and out of favor every few decades. They were very prominent in sitcoms of the 90s. The devices that generated canned laughter were invented to simulate the feeling having a live audience when performers performed first on stage but later in studio programs. If you pay attention, it does have an effect of nudging you to want to laugh along. There’s even a niche genre of YouTube videos of sitcoms with the track removed and the silent pauses the actors leave in for the track to play are noticeable and very awkward. (Example from the Seinfield “Soup Nazi” scene).

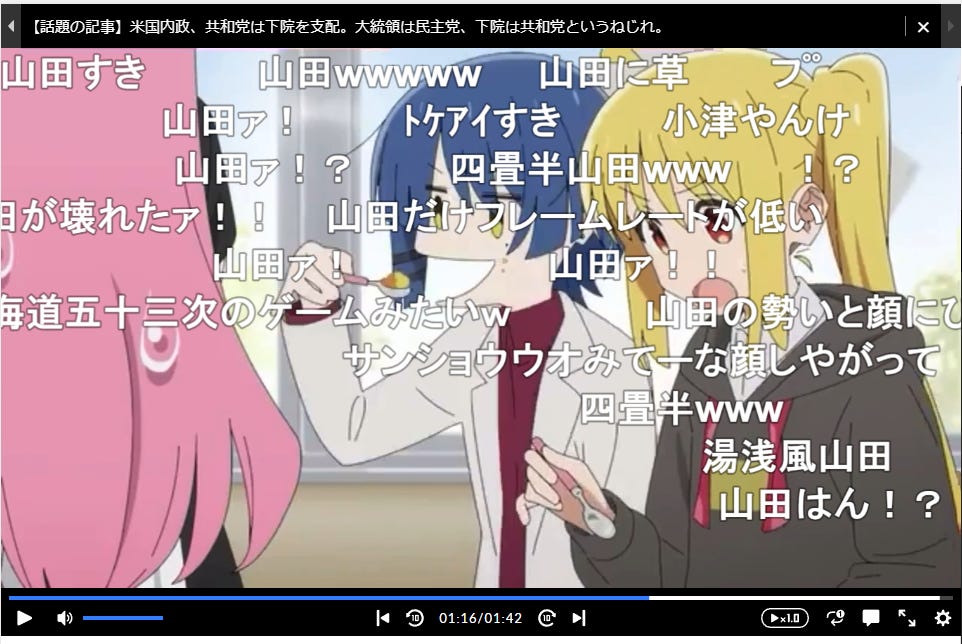

A more modern but no less in-your-face example is this video service that originated in Japan, Niconico Video. Their primary innovation was having comments of users scrolling across the video itself (there’s a lot of filtering/reporting/cultural norms going on to keep it from being a shitshow). Seeing waves of people showing surprise at a sight gag like in the screenshot below, laughing at jokes, giving applause, putting in song lyrics, or just leaving a comment increases the sense that you’re watching this video with other people even when you’re all separated in time and space. They’re believable because each one had to be entered by some human somewhere, somewhen.

Even more recently, we’ve seen innovation in meeting software like Zoom where there’s a “react” feature that lets you spam some emoji into the stream for everyone to see. It’s an inobtrusive way for people who want to give a nonverbal reaction, like showing support or celebration, to the speaker without interrupting. It also lets everyone else know that there’s other people around and paying attention — we’re not all muted and alone at our desks with cameras off.

How Normconf kept things feeling “live”

While social media was definitely a thing, with people tweeting and tooting about the event throughout the whole day, the center of the whole event was the conference Slack that had over a thousand users registered to it at the peak. Also important to the experience was that while the slack had tons of channels for memes, sharing work, and asking questions, everyone gathered in the central #general channel for talking about the conference was it was going on.

On top of audience participation, the speakers and MCs were also actively monitoring the chat rooms, often while on air, to provide a feedback loop between the audience and people visible on screen. Often, someone would pose a question, the MCs pick it up to ask on stream, the speaker would answer it, and while that’s happening, other people in the audience would chime in with their own answers. Such interaction is not even possible in an all-in-person format. It’s much more a community than even a traditional talk experience.

Behind the scenes, to keep up with the flurry of messages, the staff had been watching the chats for questions and threading them so they wouldn’t get scrolled off before MCs could notice. Staff sometimes even provided some questions on their own in case some gap-filling time was needed.

It’s not particularly difficult work, but it’s definitely a team effort to keep the production running as smoothly as it did.

While all the above sounds almost trivial and self-evident, it apparently isn’t as obvious to many conference organizers. I’ve personally attended other events where centralized chat was at most an afterthought, or worse, nonexistent. Maybe they assumed people would just use Twitter or something, which is far too scattered and async to build a community around

Some even more egregious “hybrid” events (luckily not in data) didn’t even stream all the speaker tracks, making virtual attendees third-class citizens. If that is currently where the bar is for conference events, it’s no wonder that a lot of the feedback about the conference involved people saying how much they felt involved and engaged compared to other events.

But why does this matter to you?

Because if you’re attending an online conference in the future, I want you to know that if you participate in the shared spaces, you make the conference better not only for yourself, but everyone else! In an in-person conference, all you have to do is be physically present and that alone gives much-needed validation and support to nervous speakers. It’s tempting to do the same at an online event and merely show up. But the work of interaction can’t be completely put onto the conference staff and volunteers — it takes an audience that is willing to take the opportunities created by the conference and make conversation.

We had a great experience at Normconf because when we the staff gave a shout out to the audience, the audience responded. So I’d like you to at least consider clicking that clap emoji, or typing that speaker question into the chat of the next conference you attend. It matters.

The other reason will probably apply to fewer people. It’s now easier than ever to run a small data event like a meetup of 10-25 people. It’s only a bit more work to make a medium-sized event going into 100. Just pick a topic, share it amongst friends and colleagues and snowball the attendee and speaker lists. Ask a friendly “influencer” if they’d like to share it with their followers.

But whatever size event you plan, keep in mind how to provide the “obvious” things that make gatherings of people enjoyable — that sense of “being in the same place with others”.

Do that and you’ll have something just as fun as Normconf.

If you’re looking to (re)connect with Data Twitter

Please reference these crowdsourced spreadsheets and feel free to contribute to them. Given the recent scare over the weekend, it’s good to have a backup plan.

A list of data hangouts - Mostly Slack and Discord servers where data folk hang out

A crowdsourced list of Mastodon accounts of Data Twitter folk - it’s a big list of accounts that people have contributed to of data folk who are now on Mastodon that you can import and auto-follow to reboot your timeline

Standing offer: If you created something and would like me to review or share it w/ the data community — my mailbox and Twitter DMs are open.

New thing: I’m also considering occasionally hosting guests posts written by other people. If you’re interested in writing something a data-related post to either show off work, share an experience, or need help coming up with a topic, please contact me.

About this newsletter

I’m Randy Au, Quantitative UX researcher, former data analyst, and general-purpose data and tech nerd. Counting Stuff is a weekly newsletter about the less-than-sexy aspects of data science, UX research and tech. With some excursions into other fun topics.

All photos/drawings used are taken/created by Randy unless otherwise credited.

randyau.com — Curated archive of evergreen posts.

Approaching Significance Discord —where data folk hang out and can talk a bit about data, and a bit about everything else. Randy moderates the discord.

Support the newsletter:

This newsletter is free and will continue to stay that way every Tuesday, share it with your friends without guilt! But if you like the content and want to send some love, here’s some options:

Share posts with other people

Consider a paid Substack subscription or a small one-time Ko-fi donation

Tweet me with comments and questions

Get merch! If shirts and stickers are more your style — There’s a survivorship bias shirt!

Yup, nothing will replace the business that happens over lunch/dinner/drinks at a physical event. I would help if we normalized people initiating contact with each other after having gone to the same virtual conference, but that's a lot of culture to change

I always felt like the greatest benefit from in-person conferences was the interactions in the hallway. I got a lot of business transacted there that would not have otherwise happened. Which the online conferences don't really provide - sadly.